Mark Templer Teaches Trust at a Leprosy Colony in Delhi

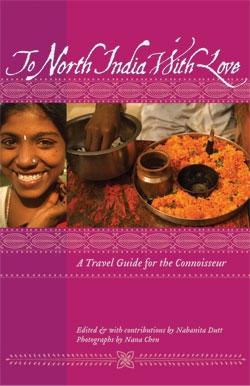

Excerpted from To North India With Love, available from ThingsAsian Press.

When I first came to India in 1985, I saw a man afflicted with leprosy in Bangalore. My initial reaction to the sight of his open sores and disfigurement was no different from anybody else's-I wanted to walk away as quickly as possible and pretend that I hadn't seen him. But for some reason, I couldn't do this. Instead, screwing up my courage, I reached out to hold one of his damaged hands in mine. I could feel two stubs where his thumb and index fingers used to be, but I did not loosen my grip. After all, the only way I could show him I was not repelled by his condition was by touching him.

It was only after I was back at my hotel that I had a full-blown panic attack. What if I contracted the disease? I kept washing my hands, over and over again, praying that I would be spared.

I knew nothing about leprosy back then. I was ignorant, and I am ashamed about how I handled my first encounter with it, although I understand how such a reaction can happen. Yes, leprosy is ugly. It starts out as a light patch on the skin, and then it spreads, destroying the nerves, so that the blood system collapses and the tissues die. Victims of leprosy lose their fingers, toes, hands, feet, eyes, and nose. Eventually, the disease burns itself out and leaves its victims grotesquely disfigured. It is fear of this disfigurement that makes people shun leprosy victims. They do not understand that the disease does not spread by touch, and they do not know that leprosy is curable-through drugs that cost just a few dollars.

The information is all out there, but it will be a long time before society finally accepts leprosy victims with a sense of humanity, and leprosy as a manageable disease. Until that happens, patients suffering from this condition will continue to live like outcasts, grouping together in appalling conditions in their shame and poverty, afraid to show themselves for fear of public ridicule and mistreatment.

Through my organization, the HOPE foundation, my colleagues and I had already started working with leprosy patients living on the streets of Delhi when the daughter of the then-president of India, Padma Venkataraman, took us to the city's Tahirpur colony-the largest colony of leprosy patients in India. More than four thousand had collected here after being thrown out by their families. Not all came from uneducated, impoverished backgrounds. Among their numbers, we were surprised to find people who had held responsible professional positions, such as university lecturers and doctors. It turned out that even those who were privileged and living in clean, healthy environments could be susceptible to the disease.

The Tahirpur colony was a mess, with open sewers everywhere. The inhabitants lived in filthy huts without electricity or water and survived by begging on the streets of Delhi. Drug abuse and alcoholism were rampant, and murders were a regular occurrence. Lack of hope for a better future fed the victims' tremendous rage against the society that had abandoned them.

In the early days of our work with Tahirpur, people were very skeptical about what improvements we could possibly bring to this black hole of disease and depravity. We had some funds from the United States that we wanted to use to build proper houses, but no one believed we could complete such a project. It would be foolishness to expect any support from outside. So we fell back on our own courage.

There were roadblocks everywhere we turned. I remember how contractors cheated us, mixing sand with the cement to save money. Before the houses were completed, one of the roofs caved in, breaking the thin thread of trust we had worked so hard to establish with the leprosy victims. After that, it was hard to convince them that the houses we were building would be safe. To prove ourselves, our architect, Joshy Jose; program manager, Ian Correa; and I decided to be the first to sleep in one of the new homes. In a nearly completed, mosquito-infested structure the three of us spent a night on the floor. The victims' fears were allayed, and they agreed to move in.

It was the small considerations that went a long way in building and maintaining trust. For instance, I would take my children to eat at the homes of leprosy victims-an action that proved my acceptance better than any amount of verbal assurances would have. Over the years, we managed to get the city to provide sewers, electricity, and roads. We housed every victim we had started the project with. We planted trees, helped start a school, and worked hard to show our love for the people of the Tahirpur colony.

Little by little we saw the community change. Drugs disappeared. Health improved. The murders stopped. People quit begging. The colony is now integrated with other neighborhoods in the area. Many leprosy patients have their own businesses. Tahirpur is a happy place. Or, at least, as happy as such a place can conceivably be.

Symptomatic of the turnaround was the colony's response to the tsunami that hit India on December 26, 2004. The patients collected clothes and cash and donated it to the prime minister's tsunami fund. From embittered beggars they had become givers. It was marvelous to see how confidence in their ability to live like human beings again had returned them to their rightful place in society.

FACT FILE:

HOPE foundation

For its City of HOPE in the Tahirpur colony, the HOPE foundation desperately needs funds to keep their bandaging, vocational training, sanitation, and dental care programs running. If you want to volunteer, give money or other necessary items, or just visit (and hopefully spread the word), visit the foundation's website. Information on the colony can be found in the Delhi I VoH listing in the "locations" section.

http://www.hopefoundation.org.in/

About leprosy

Leprosy is a progressive disease that affects skin, limbs, nerves, and eyes. If left untreated the disease spreads. Throughout history lepers (patients with leprosy) have been ostracized by their communities and even their families. Patients were literally thrown out of the house for fear of the whole family being treated as outcasts. Indians believed-and a large section of the population still does-that you can contract leprosy simply by touching a leper. This is not true.

Caused by a bacteria, most types of leprosy do not spread just by touch. What's more, leprosy is now completely curable with an ordinary multidrug therapy. Patients are no longer infectious after the first dose, and they can be completely cured within six months. If the diagnosis happens early then physical damage and disability does not occur. Now that treatment is so easily available, leprosy should not have such a stigma, but the Indian mind-set is such that lepers rarely have a second chance at life, which is why they live in "colonies." NGOs like HOPE are not only working to improve the lot of patients but fighting to get them social acceptance as well.

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian