Traditional Tet Paintings - Dong Ho Prints

You may have seen them before. They adorn the walls of Vietnamese restaurants everywhere in the world, there may be one hiding by the cash register at the neighborhood Vietnamese business, your Vietnamese friends hang them up as Lunar New Year approaches. In Vietnam, production of these folk paintings peaks right before Tet as merchants stock up in anticipation of heavy customer demand. These paintings are traditionally used to decorate homes for the New Year festival.

We have purchased many of these prints before in the local stores and markets in Hanoi and have often wanted to go visit the village they are made in. We set out one morning with a rented car and driver, and some simple directions.

The Road to Dong Ho

The village of Dong Ho is in Ha Bac, the province just north of Hanoi. We quickly leave the city and are soon traveling in the countryside with beautiful rural scenery rolling by. The 50-kilometer ride should take about one and a half-hours, if you know where you're going. We got pretty close with our simple directions. Then, we started doing what people everywhere in Vietnam do, we stopped every ten minutes or so and asked for directions. A farmer with his water buffalo directed us toward the first important landmark--a dike. We drove on the dike for a while before we ran into three school children who thought maybe we should have gone the other way. A few short stops for directions later, we spotted a village. This must be it. The only problem is how to get off the dike and head toward the village. After a few minutes of driving without seeing a road that would take us where we wanted to go, our driver exhibited another great national trait--pragmatism. When he spotted a flat area, we just drove off the dike, onto the embankment and made a beeline toward the village. Soon we found a dirt trail and were heading for Dong Ho--we hoped. As we got closer, it looked like a cluster of about fifty or so one-story houses with one large one, obviously of recent construction. We headed for the large one, a two-story building with a gated courtyard. The gate sported a sign proudly welcoming us to the place where Dong Ho paintings are made. We had arrived.

The Village

The occupants are busy opening the gate and waving us in. (They heard us coming. Not many cars make it to Dong Ho.) The whole place is buzzing, making prints. A batch is drying in the sun; several are being painted in sequence with different colors, in the shade and inside the open-air building.

We got out of the car and stood for a minute to take it all in. We had expected a village in the middle of nowhere where artisans have been practicing the craft of making prints since the 17th century. Instead, we just parked our car in the shade of the gated courtyard, walked toward the new building and were welcomed by a man who was obviously the owner and invited to come into his showroom.

After a nice chat and many cups of tea, the owner, master artisan Nguyen Dang Che, offered to take us around his complex, to watch the process of print making the Dong Ho way.

The Print Making Process

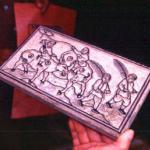

The prints are made by brushing paint made of local material onto carved wood blocks, then pressing the blocks on paper. The print is left to dry after each color is applied before another color is added. Three to five colors are used to make each print.

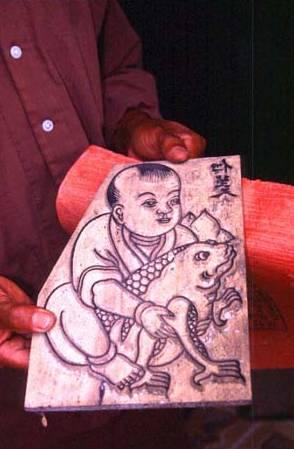

The Wood Blocks

The wooden blocks are made from the thi tree, a soft fibrous wood. The block is used as a printing plate, with one block for each color, print and size. A big shelf in the printing room holds hundreds of wood blocks. The master shows us several blocks that have been in his family for over 200 years. Wood block carving is an art handed down within the family by the master to his children. This master's family has been making prints for many generations. He proudly points to his three sons and several daughters who are busy working, learning the craft from him and carrying on the family tradition.

The Paper

The prints are all done on traditional giay gio paper made from the bark fiber of the do tree. This tree grows in the northwestern part of the country. The sheath is stripped off the tree trunk and soaked in a pond for a month. It is then dipped in limewater for two weeks, followed by a wash. After ten days or so the pulp is poured into frames which are stacked for several more days. Then the stacks are arranged on a wall to dry, and pressed smooth with a stone mortar.

The paper is coated with a pulverized powder made from shellfish found in the Hai Phong area. The shellfish is brought to the village and coated with mud for two years. The entire mixture is then ground up by stone mortar and put into a water tank to be filtered and pressed into balls that weigh about a kilo and they are left to dry on the walls or floors. They are then used as needed and mixed with glue. This mixture is called diep powder.

The Brush

The prints are painted with a beautiful brush made of spruce. The thet brushes are made from dried spruce leaves bound together. These brushes are made in a village not far away and come in various sizes. The leaves are pounded with salt water and a hammer to make the brush tip soft enough and are bound together and flattened at the top.

The Paint

The folk art simplicity has strong and simple contours with bright colors that are made from dried bamboo leaves, the local fruits, flowers and leaves. The paint is mixed in large earthenware pots. The colors are mixed by hand and each artisan has his or her own formula. The red paint is made from soi son, a soft stone that is found in the region. The blue paint is made from indigo leaves found in the minority areas. Both of these paints must be soaked in an earthenware pot for a couple of years and strained of all impurities.

Yellow paint usually comes from the sophora tree whose flowers are as small as rice kernels. The flowers are roasted in a pan until they turn brownish-yellow. When water is added and the mixture is boiled, the yellow color appears. The liquid is filtered and the pulp thrown away. The violet color comes from the mong toi fruit. Black paint comes from the bamboo tree. When the bamboo trees shed their leaves, they are burned to a cinder, then sprinkled with water and put in a glazed clay jar half filled with water. After a year or more the water is strained and the black ink is ready for use after being mixed with glutinous rice glue.

Grinding glutinous rice into a fine powder and mixing it with water makes the rice glue. As the rice powder settles to the bottom, the clear water is skimmed off every day, to prevent the contents from fermenting.

The Stories

Each print tells a story of historical significance. The prints are used to carry on the cultural history of Vietnam, passed on at the welcoming of each Lunar New Year to younger generations through story telling. The themes of happiness, good luck, fertility, good fortune and prosperity are common. They celebrate the optimism for the coming New Year.

The New Dong Ho

There was a time when every family in the village was involved in printmaking. Today, modern Dong Ho village is quite diversified. The village is prosperous, agriculture is abundant in the rice and cornfields nearby and carpets are made from cornhusks. Only some of the families continue to produce Tet prints year-round, transporting them to Hanoi for sale to wholesalers who distribute them all over the country, keeping the tradition alive.

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian