Rock and roll is a country all of its own. It has territories everywhere in the world, each with its own flavor but all governed by the hard-driving rhythm and hard-living life of the founding rockers. Wherever travelers find themselves, they’re certain to find a bass guitar, a drum kit, and a lead who fills a room with words that may be indecipherable but who clearly conveys hot sex.

Rock legends usually die young and the official cause that’s written on the death certificate is almost always drugs. Robbie Robertson of The Band sees it differently and he is a man who would know. His belief is that it’s not the drugs, it’s not the music, it’s “the road.” Like baseball or ballet, rock and roll takes athleticism and stamina, but with a schedule more demanding than many other disciplines. Its musicians never go offstage. Their lives are ruled by the realm that they’ve chosen. In that way they are very similar to priests and the government that most closely corresponds to rock and roll is the Vatican. After those comparisons are made, all bets are off. Priests usually achieve longevity but in rock and roll, there are few Mick Jaggers.

Thailand is a perfect outpost for rock and roll. The freewheeling lifestyle has been perfected over centuries of diligent practice, the women are beautiful, the alcohol is cheap and deadly, and the climate is ideal for growing poppies. When soldiers showed up during the Vietnam War, they came bearing their own soundtrack and near secret air bases along the Mekong river, kids who were raised on the wild twanging sounds of Thai country music grabbed onto rock and roll and never let go.

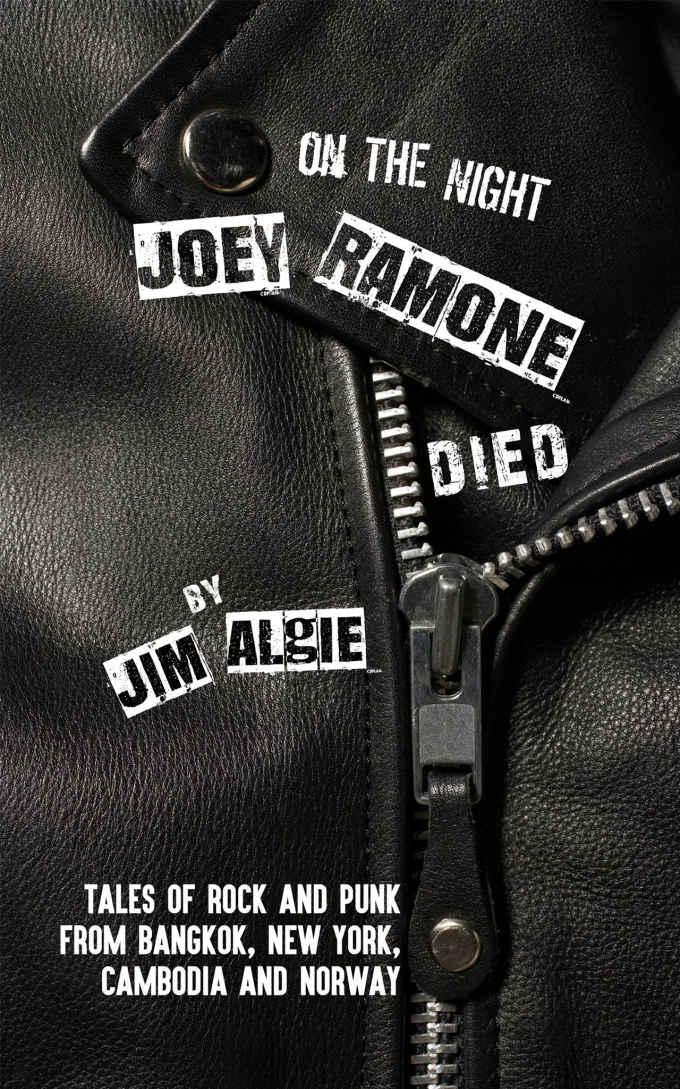

Fifty years later it’s still there. And the kids who became its first inhabitants? There are the survivors like Lam Morrison and the ones who died, who are legion, and then there’s the leading character in the new novel by Bangkok writer, Jim Algie, On the Night Joey Ramone Died.

Lek produces albums for syrup-voiced boys whose looks outweigh their talent. His musical heroes are “dying of diseases instead of overdoses” and, as he remarks to a contemporary, “...fifty seems young.” Lek himself rankles under the criticism of his ex-wife who told him “You’re not a punk or a rebel anymore….You’re a businessman in a leather jacket and torn jeans.” His drugs now are cigarettes and coffee, which may kill him but distinctly lack cachet, and his teen-age son Dee Dee is blatantly unimpressed. It would be the perfect Woody Allen scenario, but this is rock and roll and Lek is still “crazy after all these years.” After all, he uses Barbie and Hello Kitty dolls as target practice to let off steam.

Then his son’s English conversation teacher walks through the door, a small blonde Norwegian girl who dresses like Jim Morrison’s girlfriend, swears like a rock star, once lived down the street from Alice Cooper, and is a death metal fan. She’s smart, funny, and dark as hell--and she likes Lek.

Suddenly middle-age doesn’t look so bad, now that he’s got a cute chick, lines of coke, and lots of booze in the mix. Lek begins writing songs again. But who’s the girl who has come into his life and what lies at the end of this new road?

“Write about what you know,” is the leading cliche of English 101, along with “Show, don’t tell.” Jim Algie knows more about rock and roll, Bangkok, and the enticement of a killer lifestyle than many, and he shows every corner with talent that is almost cinematic. Lek’s nightmare world is one that Martin Scorsese would commit homicide to have, revealed with wit and undertones of Chet Baker, a blood-red place in the ninth circle of hell where Pol Pot links arms with Cannibal Corpse and Death comes out the winner.

Put this one on the shelf with Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me and Beautiful Losers, drink a toast to Janis, Jimi, and the Lizard King, and hope like hell that Jim Algie is working on that next novel. “There’s more to the picture,” and he’s the guy who knows enough to show it all.

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian