An Artist and Her Work: Dinh Y Nhi

Nguyen Qui Duc visits with Hanoi artist Dinh Y Nhi

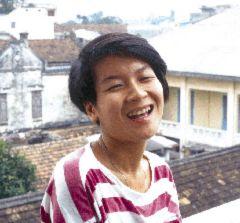

There is in Dinh Y Nhi's paintings a sense of maturity and confidence that's astounding. The surprise comes in part from the impression the painter creates of herself: she appears deceptively young and naive, and frequently adopts playful ways of talking.

At her age, Vietnamese women are more likely to be a serious mother of two or three, worrying about a job, meals, and household chores. Y Nhi keeps all worries from her face, and her hair is cut short on one side, almost in a boyish crew-cut style. The 27-year-old painter and professor of aesthetics is without pretension as an artist who deals with the sorrowful human fate.

Dinh Y Nhi is a graduate of Hanoi's School of Fine Arts. Her father, the much-decorated painter Dinh Trong Khang, has been teaching there for more than 20 years and lives with his family in an airy apartment toward the back. Her mother works for the motion picture industry. Y Nhi's father was her first art teacher, giving her lessons before she was nine years old.

Y Nhi's current series consists of dozens of large gouache paintings on paper. Her subjects are child-like stick figures, or cartoon faces, rendered with deceptively random and simple brush strokes. There is a playfulness that reflects the outer images the painter projects of herself. But the paintings are haunting.

The stick figures are warped and elongated - stretched out of proportion - and the arms and legs look like long and smooth bones. Each figure tilts and twists at painful angles. They bring to mind the famous harrowing faces in Edward Munch's The Scream, or the difficult distorted ones from the portraits of Francis Bacon. But most of the faces Y Nhi paints are miniature ones devoid of details. And they are in black and white.

"I do look for simplicity in my paintings," says the painter, explaining her decision to use only black and white - and moody shades of gray - for her current series. The limited palette does conform to the cartoon figures she represents in the paintings, but Y Nhi's style also allows her to convey complex textures, and emotions, in her images. The shades of gray contribute to a soothing fluidity. And they provide a contrasting context and perspective to the otherwise one-dimensional and flat figures.

What is most astonishing is Y Nhi's ability to imbue such flat characters with alertness and extreme expressions. In some of the larger faces, the eyes are at once thickly outlined and hollow, inevitably reminding one of a skull while appearing incredibly alive. As simple as they appear, Y Nhi's cartoonish characters defy us to approach them and judge them in any other way but with the most serious intentions.

They all seem bound together by the same fate, and theirs seem to be an expression of shock and terror. "I don't know," Y Nhi replies when asked about the reason for such expressions. When I visit her the second time the next day, I bring up the question again, seeking to find out whether Vietnam's turbulent past had influenced her depiction of such characters.

"I didn't set out to paint people who are facing any horrible circumstances," she says simply. Then she smiles and mumbles something that's lost in a chuckle. I can't get her to say it again, so turn to contemplate the faces in the paintings. I notice that none of them carries a smile. And cartoonish as they are, they each have been rendered with unbelievable individuality.

"Look around," Y Nhi suggests. "We all have the same features: a pair of eyes. Eyebrows. A nose. A mouth. But yet each one of us is so very different , don't you agree?" She smiles. "You don't look like me, I don't look like my friend."

By reducing human beings down to their simplest features, she actually highlights the physical differences, while simultaneously showing us how we are bound together by the same fate and conditions. In one eerie piece, the faces are lined up in square boxes, like ID photographs stuck on a wall. As with her other paintings Y Nhi has made the faces individualistic, suggesting a private history to each person in each square box. But once again, by placing the boxes in a grid and making them repetitious, she has given them the same fate. The painting looks remarkably like the walls in countless Vietnamese temples - with photo portraits of the deceased all pasted upon the wall, forming a shrine above the urns containing their ashes.

Another equally disturbing painting shows three people inside rectangular boxes that could pass for coffins. I mistakenly refer to the cross above their heads as the Catholic cross. "It's the plus sign," Y Nhi corrects me. The idea for the painting came from recollections of her high school days, when she was a talented math student. "I simply thought, what if instead of numbers, we added people together?"Y Nhi's questions, as I find out through later conversations, are usually simple. But they yield no easy answers. She never answers them herself, neither do the paintings, which makes it almost impossible to turn away from them. The questions stare at you, and don't go away.

Y Nhi's simplicity with her words translates into an ability to bring out the essence of what she sees by simplifying the details. Her oil paintings consist mostly of buildings - stripped bare of details such as windows, doorways, or shadows.

As part of her "di thuc te" training, or "real life field trips," Y Nhi got to travel to several cities in Vietnam. "A lot of people merely paint what's in front of them. But I can only see what I see."

In Danang, the largest urban center in central Vietnam, she saw the first tall square-block buildings of her life. "I needed to simplify them," she explains. The results are blocks of pale colors, faintly outlined, with perhaps a red roof or an off-white wall as the single feature. The chaotic urban architecture is reduced, and suggested, but what confronts the viewer is still an imposing and sterile environment. There are no trees or people to soften the image, and the coldness of such an environment is only made bearable by Y Nhi's use of warm tones. All colors had been mixed with white. Artists familiar with Y Nhi's work often praise her originality. "In the increasing commercialism of the Hanoi art scene, more and more artists are painting what sells," says Le Anh Van, a painter and professor at the School of Fine Arts and also Y Nhi's neighbor. "But Y Nhi has developed her own style, her own expression. I am amazed at the confidence she displays in her work, considering that she is still so young.

Other artists express the fear that someone as young as Y Nhi may get stuck in a particular style. Comfort, not to mention early success, often blocks an artist's development. While he shares that view, Le Anh Van is optimistic about Y Nhi. "She will grow. She works hard."

Y Nhi spends a couple of hours a day teaching a course in aesthetics at the school of architecture in Hanoi. She also spends an hour or two a day learning English in anticipation of a possible exhibition tour in the United States. Y Nhi is now anxious to have a larger studio. Her current workspace is actually the landing on the stairwell leading to the rooftop terrace of her house.

Y Nhi's work has been exhibited in many shows in Vietnam and recently she was part of a group show in Bangladesh. She is receiving much notice among the Vietnamese press and art patrons in the United States, Australia and Asian countries. The black and white paintings with the stick figures are attracting collectors willing to pay prices considered high for Hanoi's art market except for works in oil by truly talented and well-known artists. In the end, the paintings are irresistible because Y Nhi successfully allows such intense human emotions as sorrow and fear to inhabit the faces of so deceptively simple black- and-white characters.

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian