The Changing Face of Chiang Mai

No more than twenty years ago, children played badminton on Prapoklad Road, near Chiang Mai's gate bearing the city's name. Their families got their essentials from the "fresh market", an enormous, dimly-lit covered market selling everything from shoes to raw meat to electronics. There were no supermarkets to speak of, still less department stores, malls, or Wal-Mart-like "superstores." Travel was commonly conducted via cycle rickshaw. Prapoklad was fairly quiet most of the time.

Now this same place is noisy and congested. One would not dream of playing badminton here. One would need to go well outside of the moat that girds the old city, or deep into its labyrinthine network of narrow roads, or "soi's". While families still get food from the fresh market, durable goods are more likely to be bought at the Central mall, Robinson's department store, or at one of the - usually foreign-owned - superstores like Makro, Carrefour, and Lotus. Travel is conducted via privately-owned cars or the more common motorcycles. Barring these, one takes a "tsong-tao" -- a red or yellow pick-up truck whose bed is fitted with benches and capped by a metal roof - or a "tuk-tuk" -- the propane-fueled three-wheeled "autorickshaws", so-named because of the "tuk-tuk" sound of their exhaust. Cycle rickshaws are rare. Pedaled amidst harrowing traffic by elderly Thais, they are generally taken only by elderly Thais, or tourists in search of anecdotes.

While much of Thailand's development has centered in Bangkok, it has always spilled over into Chiang Mai (CM), and for good reason: Thailand's second-largest city, the latter is generally regarded as a resort town for fatigued Bangkokians. As a result, it is becoming more like Bangkok every day. Inside the moat, the air and noise pollution and congestion are comparable; high rises are perennially under construction; and the population has exploded.

While Bangkok's population explosion may largely be attributed to an influx of upcountry Thais in search of opportunity - many of them from CM itself - the explosion in CM is due also to an influx of Burmese refugees and the effectively self-sovereign hill tribes: Hmong, Akha, Lisu, et al. To these groups, CM is the nearest, least politically volatile, and most prosperous city. Bangkok, for all its glitter and work opportunities, is increasingly seen as unbearable. As the CM Thais move up the economic ladder, these groups appear in the low-paying jobs characterizing its bottom: waitstaff, janitors, prostitutes.

The old city of CM is contained within a brick wall, with a moat running along either side. Thus the city's expansion has led not only to an intensification within the wall, but also to rapid, leap-frog development without it. But the wall is hundreds of years old, so however much it may contribute to congestion in the old city, it is probably there to stay.

Very little has been done to mitigate the sharp increase in traffic. The city government is elusive at best. While many other Asian cities have made restrictions on vehicles permitted in their downtowns - Bombay, for example, banned its autorickshaws to the suburbs - CM has made none. Recently there was talk of a subway system - apparently inspired by the celebrated, but much-postponed completion of Bangkok's SkyTrain - but not for another decade. Given the snail's pace of the SkyTrain construction, twenty years would probably be more accurate; and, in any case, the SkyTrain is having trouble staying financially viable.

Meanwhile, a grass-roots effort to encourage the use of bicycles - CM's small scale is ideal for them - is usually met with incredulity. The usual, all-too-human rationale is that the air is too bad and there is too much traffic. People buy cars so that they can breathe unpolluted air. And while the city recently painted a number of lines on busy roads to demarcate bicycle lanes, most are covered with parked cars or noodle shops.

This apparent slowness to act is due to the breakneck pace of Thailand's industrialization. As the saying goes, people simply don't know what has hit them. While progressive Westerners are seeking alternatives to the cars they already own, Thais are eager to purchase their first -- car ownership being almost synonymous with having "made it." It matters little that CM was not built with BMWs and unwieldy Land Rovers in mind; they multiply like rabbits in a cage of unchanging size.

One attempt to respond to the traffic has been moderately successful: the construction of the Super Highway, a road of two or three lanes in either direction, encircling the old city and providing an alternative to passing through it. As little as a few years ago, this road saw little traffic. Now it is showing signs of obsolescence. And the large-scale multinational industries and stores that have sprouted around it make CM's purlieus eerily resemble those of Bangkok, or, for that matter, Los Angeles.

Another sign of CM's Bangkokification is its increasing overpasses. Many of these are around the Super Highway. One, still under construction near the CM airport, remains controversial. It will form part of the highway linking CM to its southern sister city of Lamphun. The project was approved without a public hearing, and the overpass will obstruct the view of the eye-pleasing Airport Plaza. Many fear that these "cement rivers" will wash away the old charm of CM forever - to say nothing of sleepy Lamphun.

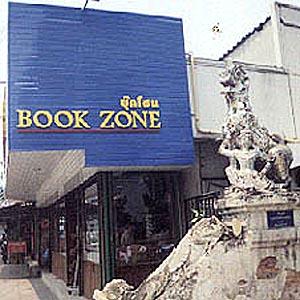

CM has also seen great changes wrought by its being the tourists' gateway to northern Thailand, Burma, and Laos. Since the Asian financial collapse made Thailand an eminently affordable travel destination, the economy of the area around Thapae Gate has geared itself almost entirely to tourist traffic. Constantly appearing are Thai language and cookery schools, travel and trekking agencies, massage parlors, Internet cafes, a host of foreign restaurants, and guesthouses -- many former family residences, converted within the last few years.

The red-light districts are also fairly new. Twenty years ago, Loi Kroh Road - now the port of entry for tourism one writer has dubbed "whorism" - was all but empty. Now it contains nearly a score of bars with names like "Butterfly" and "Cherry." The district has leapt across the moat, and extends well into Night Market - almost everywhere tourists are likely to tread. A city said to contain nearly 200 Buddhist temples, CM has even more bars.

To be fair, this traffic has the benefit of making CM a remarkably cosmopolitan place, despite its small-town feel. Of the many tourists who fall in love with CM at first sight and decide to make it their home, many want to see it improved, and do so through whatever channels are availed: NGOs, conspicuous bicycle-riding, "fair trade" co-ops employing hill-tribe women who might otherwise become prostitutes. But foreigners cannot legally own land and have no sanctioned political power. As long as tourism is Thailand's primary source of foreign exchange, its ill effects may grow unchecked.

For all its change, CM remains a unique place. It is bustling, but avails many quiet sois for retreat. It is deeply Thai, but has a lively, varied, and supportive expatriate community. It is small, but big enough to have the cuisine of Italy, Mexico, and France, to name a few; current movies and cultural events; and just about anything you could hanker after.

But, for reasons partly associated with CM's descent into kinship with Bangkok, I soon will leave it and go south. Twenty years ago I might have fled Bangkok for CM; but that CM is gone, and nobody - myself included - exhibits the will, stamina, and clout to wrest it back.

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian