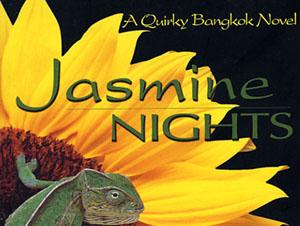

The Not-J.D. Salinger of Siam: S. P. Somtow's Jasmine Nights

Elsewhere I have mentioned the irritating habit of reviewers to compare second-rate authors to The Greats, as in "the Hemingway of Bangkok." Now I see that George Axelrod, screenwriter of Breakfast at Tiffany's, has read S. P. Somtow's Jasmine Nights and dubbed Somtow "the J. D. Salinger of Siam". Sigh. What's next? "The Faulkner of Burkina Faso"?

To understand how the unfortunate Salinger comparison could have been made, it might help to recall that Breakfast at Tiffany's starred Mickey Rooney, that celebrated Asian actor, in the role of an offensive caricature: a buck-toothed Chinaman, who called Audrey Hepburn's character "Go Rightry" instead of "Go Lightly". This puts into serious question Axelrod's expertise on matters Siamese, I think. (Okay, it was 1961 - but still.)

As for the Salinger part: Salinger published four books, mostly about Jewish-Irish neurotics in New York City. His tone tended to be a mixture of giddy sarcasm (Seymour: An Introduction) and suicidal melancholy ("A Perfect Day for Bananafish"). He then went up in a cloud of misanthropy and fled to upstate New York, never to be heard from again.

Somtow has published over 40 books in several genres -- including horror - and their settings have included Los Angeles and Bangkok. Jasmine Nights, at least, has little of the sarcastic or melancholic about it. It is a farce, and an excellent one. As for Somtow, when he is not writing shelves full of books, he is composing world-renowned symphonies and is very much in the public eye. The International Herald Tribune called him "the most well-known Thai expatriate in the world."

There are only two characteristics that Salinger and Somtow conspicuously share: their erudition, and their tendency to favor the idealism of children to the "phoniness" - to use Holden Caulfield's word - of adults. But when Holden said "phony", he did not mean "funny" - he meant "fake". Jasmine Nights's narrator - a prepubescent Thai aristocrat named Little Frog, more at home amidst the "topless towers of Ilium" than in 1963 Bangkok - is able to laugh at adults in a way that sad Holden could not. "While adults cannot comprehend the importance of a chameleon's friendship," says Frog, "they do attach immense value to footgear. Perhaps it is because they are incapable of abstract thought." As for erudition, Jasmine Nights reads as though Somtow flipped through the entire Great Books of the Western World with one hand while he wrote with the other. Mostly the effect is charming, as when Little Frog refers to his prissy, eternally eaugh-ing aunts as the three Fates. But sometimes Somtow appears merely to be reminding us, on every page, that he was educated at Eton and Cambridge, unlike the Thai street urchins described here: "Children with sponges have swabbed our windscreen and are thrusting garlands of jasmine in our faces, while a water buffalo is licking the hood ornament of our Studebaker. These familiar sights do not interest me."

Jasmine Nights is a "coming-of-age" story. But intellectually, Little Frog is already of age. He speaks as though he has already read at Cambridge, not as though he were still innocent of Eton. Consider this doggerel from Little Frog's first swipe at playwriting:

"Ye puny mortals sitting down below, Know ye that I, blind Homer, prince of poets, Am come to relate a tale as old as time. Listen, ye mortals! Listen now, and learn Of Helen, beautifullest of womankind.... Of Hector, Priam and lots of other people, Whom I shan't name for fear of running out Of envious and calumniating Time."

Yes, this is a professor in child's clothing -- and in a child's body, so many of Little Frog's discoveries are of that Dance of Salome known as sexuality. Or, as one chapter title has it, "Shkroovink and other S-words", the latter including sin and "self-abuse", the word a lovably repressed Catholic priest uses for -- the "m-word".

Thus Little Frog calls his member an "aubergine". Thus, in the midst of his first entanglement with naked bodies, he is "suddenly possessed by the overpowering feeling that something has got to be inserted into something.... But what must be inserted into what?" Thus, Little Frog accompanies his Western schoolmates to a "massage parlour", where his friend runs screaming from a prostitute for fear that she would - ahem - eat, as a cannibal would, his aubergine.

In The Story of Jan Dara, another well-known novel about a Thai boy's initiation into manhood, sexuality is treated as an ultimately self-destructive compulsion. No such dour puritanism infects Little Frog, though his Christian educators are contaminated. Little Frog has just announced to his biology teacher that he knows how babies are made. He doesn't know really. He says, "Well, things go into other things, and-". Nevertheless, his biology teacher boots him from the classroom. Muses Little Frog:

"It is only at this moment in my young life that I come to understand that the act of love, which in my inchoate fashion I have viewed only as something beautiful, pleasurable and earnestly to be desired, is actually supposed by many to be rather nasty, nay, evil.....It is my first exposure to the problem of sin...."

Sin is not a very deep component of Thai culture. But about Thai culture we learn a great deal from Little Frog. We learn that it is "very, very, very" bad luck to get a haircut on Wednesday, and that "in the Thai language, one cannot be inventively abusive without making constant use of alliteration, assonance and internal rhyme." We learn that even Thais can laugh at Thai nicknames:

"First come my cousins, Shrimp, Crab, Tadpole, and Lobster, and my second cousins, Red, Green, Black and White. My aunts' cousins, Jinx, Lynx and Minx and their cousins-in-law Bong-bong and Albert.... I rejoice, at least, that my parents have not seen fit to give me the nickname of Hockey Puck...."

Jasmine Nights is very much a product of the Thai aristocracy, and very much about it. Somtow himself is the great-nephew of Queen Indrasaksachi, wife of Rama VI. Of his real surname, Sucharitkul (Somtow is a pseudonym), my Thai girlfriend expresses awe. "Oh," she says. "That's a rich name." And most of the characters are rich people. Says Aunt Ning-Nong (the other Fates are Nit-Nit and Noi-Noi): "After all, we mustn't forget how much more fortunate we are than....well, than virtually everybody else." Noi-Noi chimes in: "That's the lower classes for you....You've seen one, you've seen 'em all."

But unlike other authors in the Thai aristocratic tradition, Somtow does not bemoan the aristocracy's fall from grace. Instead, he never seems to stop laughing at its utter lack thereof. As a chronicler of the upper classes, he is more Thackeray of Vanity Fair than Chekhov of The Cherry Orchard. Well, there I go with my own silly comparisons - but not so silly as Axelrod's. Somtow is wise like the Buddha. He laughs in the midst of relentless folly. Salinger is wise like Christ: he tells his riddles and then, pursued by rock-throwing Pharisees, makes for the lonely hills.

* * * * *

S. P. Somtow's Jasmine Nights, Asia Books, Bangkok, 2001.

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian