On Being Green and Vietnamese

Well-known films about Vietnam have mostly been American films about the Vietnam War. And most of these have been less about Vietnam than about America's struggle to atone for its most blatant misuse of power. I have seen only one film, Oliver Stone's Heaven and Earth, that showed the war mostly from the Vietnamese side. In that film it is America and not Vietnam that appears as a foreign and benighted land, where everyone is fat and rich but no one is very happy. But then Stone is an extremist, who proposed that September 11th was a collective act of revolt on the part of the world's downtrodden -- including, presumably, the Vietnamese.

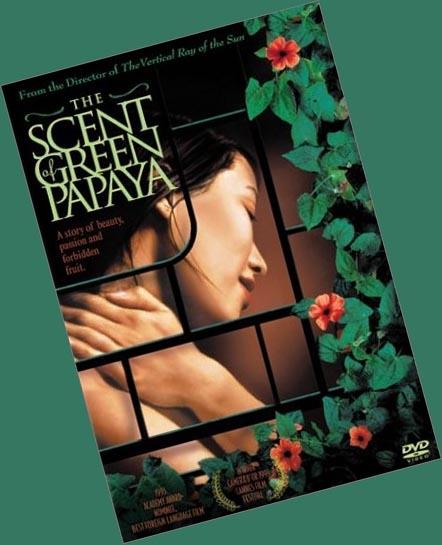

The French were just as bumbling and unsuccessful as the Americans in their attempt to subdue one of the world's most independent lands. But arguably France fell in love with Vietnam more than did America, which regarded the country as little more than a death trap for American boys. France left more good things behind: for example, architecture and the Romanization of the Vietnamese language. But it also took more good things away: not just treasures or commodities, but a lasting affection for the Orient that is like the memory of a pleasant but failed tryst. So perhaps it should come as no surprise that the only truly beautiful and artful and peaceful film about Vietnam that I have seen, The Scent of Green Papaya (1993), was created with French collaboration.

Written and directed by Tran Anh Hung, the film is set in Saigon in 1951, a few years before France's disastrous military defeat at Dien Bien Phu. But the only possible evidence of a colonial presence is the nightly wailing of a curfew siren and the occasional sound resembling jet engines. The film's credits are dominated by French names but the film itself is without them.

The story centers around a servant girl named Mui, who has recently begun her employment in the home of a family of clothiers headed up by a "Master", a "Mistress", and the Master's old and reclusive mother. The Master and Mistress have three sons. The youngest, Tin, likes to harass Mui by dangling lizards over her, urinating near her, or farting in her direction. The older boy, Lam, likes to drop hot wax on ants or crush them under his finger. Boys will be boys, except that their behavior suggests something darker. In contrast, Mui is enchanted by nature: by ants, frogs, crickets, and especially by papayas. (The film's Vietnamese title, sans diacritical marks, is Mui Du-du Xanh. Mui is identical to the girl's name; Du-du means papaya; so perhaps her name is "green", which fits with her naiveté and love of nature.)

An older and very dutiful female servant trains Mui in the ways of food preparation and service. She also relates to her the family secret. On a few occasions the Master has left home and taken all of the family's savings with him. He does not return until he has spent it all. But when he did this seven years ago, he returned to find that his only daughter, To, had died of some disease. Blaming himself for the death, he is a glum and uncommunicative man who spends most of his time playing mournful music on a stringed instrument. And he never leaves the house again. Until now.

When he leaves this time -- for some "fresh air", he says -- the Mistress is forced to sell off her precious vases and jewelry in order to buy food. Worse, her mother-in-law blames her for the Master's departure. A man will stray, she says, only when his wife is not doing enough to please him -- a recurring idea in traditional Asian culture. The two younger sons grow churlish and depressed. The mother-in-law dies. Ten years pass and the Master never returns.

Mui, now twenty years old, is sent by the Mistress to work in the house of a young, rich, and gorgeous composer. While he plays tempestuous Chopin tunes on his piano, she cooks for him and polishes his shoes. Though he already has a fiancé, he soon falls for Mui. She learns this when she discovers that he has been making sketches of her face. So does the fiancé, who reacts by throwing an ugly tantrum and leaving.

The film's skeletal and rather conventional plot is not what makes it so enjoyable to watch. Instead it is the film's sheer elegance and the obvious delight its makers derive from the natural and human worlds. It was probably for its sensuous impact that the film won the Camera d'Or at the 1993 Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for an Oscar. With the exception of the two boys, the characters are so graceful in their movements, so polite in their speech, and so attentive to small details, that one comes away from the film feeling purified. The French influence is unmistakable in the film's gentle surrealism, its abrupt and rather anticlimactic ending, its reliance upon action over speech, its studied affirmation of life despite its trials. But these could just as well be Asian influences: the film is comparable to sequence of visualized haiku.

Some of the film's most intriguing characters are its minor ones. There is Thuan, a soft-spoken old man who hangs around outside the family compound. One day he asks after the old grandmother. Later he offers Mui a fruit. Then he tells her that long ago he had proposed marriage to the recently widowed grandmother, but she refused. And ever since the death of To she has never left the house, so Thuan has been unable to gaze at her. Instead she spends all her time praying. Mui encourages Thuan to approach the grandmother, but all he does is enter the house and view her furtively from behind. He smiles and we smile with him.

The other minor but affecting character is Mui's servant mentor. Her obedience and her mastery of cooking are admirable in themselves, but she also reveals that she has an inner life and a past of her own. When Mui tells her of a dream, the old lady exclaims, "My God! I'd like to dream." But she hasn't had a dream "in ages." This I suspect is a double entendre on "dream"; one assumes that she will never be anything more than a servant. And when the ten years have passed she is nowhere to be seen.

But the film's star is of course Mui, the very embodiment of simplicity, humility, and curiosity. She keeps her head down, tries to stay out of trouble, and finds solace in creatures as insignificant as herself. It is Mui that one wants to emulate. One wants to be harmless, natural. For in proportion as one becomes these things one will be exalted. That may be the message of this exquisite and unforgettable film.

- THE END -

Review of The Scent of Green Papaya (1993), written and directed by Tran Anh Hung

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian