Encroaching Upon the Floating World: An Interview with Artist Michael Knigin

While scouring the World Wide Web in hopes of purchasing a rare, original Hiroshige woodblock print, I serendipitously happened upon the works of painter and printmaker Michael Knigin. In my quest, I discovered that between 1978 and 1982, in a series of paintings and prints inspired by the works of Japanese woodblock print artists such as Hiroshige, Hokusai, Utamaro, Harunobu, Buncho, Kunimasa, Kambara and Yoshitaki, Michael Knigin created a bridge that has spanned both time and space.

Curious to know more about Michael Knigin and the source of his artistic genius, I located and contacted him through his website, www.michaelknigin.com. And in response to my e-mail, he generously agreed to allow me to interrupt his creative process for a personal interview.

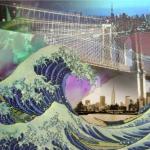

In a series of telephone conversations, I learned that the prints and paintings which first drew my attention are called "The Japanese Suite," and consist of approximately 50 paintings and 100 hand-drawn original lithographs, all with Ukiyo-e landscapes and figures in the foreground, placed against black and white photographic backdrops of the Manhattan skyline and other urban scenes.

The 50 paintings in the series were created by an innovative process, in which Michael's photographs of the city skyline were developed directly onto a special photographic canvas called Luminos. Michael then added interpretations of Japanese images that he thought to be extraordinary to the foreground by hand with acrylic and enamel paint. He did note however that, although his line drawings are quite true to the original Japanese woodblock prints, he took creative liberties with color and a myriad of textures. The result is both unexpected and compelling.

Nearly 7,000 miles and 200 years separate the floating world of Japanese Ukiyo-e, and the concrete collage that is the New York City skyline. Yet, when placed within the same context, they convey a powerful message.

"My concern with themes of comparison is continually running through my works," says Michael. "Man and nature, his continual encroachment on the natural, and the schism that that creates, the dehumanization of mankind, the old and the new, the classical and the contemporary, and the apparent lack of concern with the beautiful and the elegant in the mainstream of contemporary culture."

Ironically, Michael Knigin did not visit Japan until 2002, more than 20 years after the creation of "The Japanese Suite," although he had been invited many times and had a number of shows in Tokyo. Nevertheless he has an abiding appreciation for the Japanese aesthetic, with its emphasis on ornamentation and beauty, along with their conception of perspective, which he uses in his works to this day. Michael is not alone in his use of Japanese imagery in his artwork. The Impressionists, along with Van Gogh, Manet, the post-modernists, and many contemporary artists, have gleaned their visions from these great Japanese masters.

Michael says that although he still has a few of the prints on hand, the paintings in "The Japanese Suite" have all been sold. And these, along with many of his other works, hang in such prestigious venues as The Smithsonian Institute, The National Collection of Fine Arts in Washington D.C., The Whitney Museum in New York, The Brooklyn Museum, the Carnegie Mellon Institute in Pittsburgh, The Albright-Knox Museum, and among the private collections of the Toyota Corporation, NASA Art Collection, The Phillp Morris Collection, The Chase Bank, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, Bank of Tokyo, The Japan Society, Playboy Enterprises, and Rolling Stone Magazine.

In fact, Michael Knigin's ten-page resume reads like an artist's dream come true. His works have been exhibited in more than 25 solo exhibitions, more than 135 group exhibitions, and are included in more than 50 public, private, and corporate collections. Michael himself has also been featured in more than 50 articles and reviews, including the New York Times, USA Today, the Washington Post, the Asahi Evening News, the Mainichi News, Artspeak, Who's Who in American Art, Art In America, and the Encyclopedia Britannica.

His awards and accolades include the Society of American Graphic Artists' John B. Turner Memorial Award, the National Society of Illustrators' Certificate of Merit, Pratt Institute's Faculty Development Award, and a CLEO Award for Art Direction with Cinetudes Film Production.

Michael has also authored and contributed to several books, including "The Technique of Fine Art Lithography," which still serves as a definitive textbook in schools throughout the United States and Britain, and "Contemporary Lithographic Workshops Around the World," a coffee table book which is considered a bible in his field of expertise.

And yet, to speak with him in person, Michael Knigin's modesty and unaffected candor belie his artistic achievement and recognition. He answers his own phone, he produces his works of art in the studio complex of his East Hampton home, where lives with artist Joan Kraisky; and he still teaches weekly printmaking classes at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn NY. But his passion for his art is unrelenting.

Born in Brooklyn, New York in 1942, and growing up as an only child, the artistic muses visited Michael Knigin early in his life. He says that his creative anima manifested itself even before he entered elementary school, and he recalls entertaining himself with his drawings as a child, as an antidote to the monotonous conversations of the grown-ups, which seemed to drone on for hours.

Throughout his career as an artist and teacher, Michael has always been drawn to printmaking, especially those nineteenth-century Japanese Ukiyo-e woodblock prints. After graduating high school, Michael went on to study at Temple University's Tyler School of Art, where, in his junior year, he was awarded a Ford Foundation Grant to study fine art lithography at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles. In 1967, Michael joined the faculty of the Pratt Graphic Center in Manhattan and pioneered a fine art lithography workshop.

In 1968, Michael opened Chiron Press, his own fine art publishing company, which specialized in lithography and silk-screen prints for such luminaries as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and Paul Jenkins. And by 1974, Michael began garnering international recognition, when he was approached by the Jerusalem Foundation and the Israel Museum to establish the first professional silkscreen and lithographic workshop in Israel, for the purpose of training young Israeli artists in the techniques. Upon his return to the U.S., Michael was appointed to the position of Professor at Pratt Institute.

In 1988, Michael Knigin was invited to join the NASA Art Team to visually interpret the launch of the Space Shuttle Discovery from Kennedy Space Center, NASA's first return to space after the Challenger disaster in 1986. In 1991, he was recalled by NASA to interpret the touchdown of the Space Shuttle Atlantis at Edwards Air Force Base, and has recently been commissioned for a third work of art inspired once again by the Space Shuttle.

Since his creation of "The Japanese Suite," Michael Knigin has moved on to many other themes, including flowers, carousel horses, animals, social commentary, environmentals, vintage nudes, nudes, NASA, and his recent series entitled "Remembrance Art," a collection of interpretative collages commemorating the suffering of the Jews during the Nazi holocaust of World War II Germany. He is also working on his favorite series, Anne Frank, which is on-going today and is presently, along with Joan, working on a book with his images and quotes on the Anne's very short, but extraordinary life.

In addition to his painting and printmaking, Michael works extensively with collage, and has recently forayed into the realm of digital art. Of his work Michael says, "This "language" is not a new one...the vocabulary consists of objects and the environmental elements familiar to us, but through the various elements that I use (color, texture, symbol and fragmentation), this creation of something which is entirely new further affords both me and my audience the possibility of interpretation and personalization, as contrasted with literal interpretation."

"In my paintings and graphics, I seek to isolate objects from their mundane contexts and reorganize them, thereby granting them a new life. I select colors, textures and forms which compliment the natural forms that I use; however, these artistic elements are present to reiterate the fact that I am involved in the creation of something new, and not simply in replicating nature's truths."

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian