One Man's Love: The Taj Mahal

There are really only a few things one must do before leaving this Earth. They include falling in love; making something useful or beautiful, be it a spaceship or a sonnet; and seeing, with one's own eyes, the Taj Mahal. Not that the Taj itself is the world's premier artistic accomplishment. The Sistine Chapel inspires more awe; and the palace at Versailles is more resplendent. But these works were created to glorify gods and kings, while the Taj testifies to the glory of one woman, if not to romantic love itself.

The woman was Arjumand Bano Begam. In accordance with her status as empress of the Moghul Empire, she possessed many honorific titles - Nawab Aliya Begam, for example. But chief of these were Mumtaz Mahal - 'chosen of the palace' - and Taj Mahal - 'crown of the palace.' Mumtaz married the penultimate Moghul emperor, Shah Jahan, in 1612, when Jahan was 20 years old. She bore him 8 sons and 6 daughters before dying in childbirth on 17th June 1631 in Burhanpur, where she and Jahan had been living. She was only 39 years old.

Though Jahan had many wives (and already had two children prior to his marriage to Mumtaz), he was particularly devoted to her. A strict Muslim, a polyglot and a polymath, Mumtaz probably earned this devotion through her ability to keep Jahan in line. For after her death, the emperor's licentiousness apparently knew no bounds.

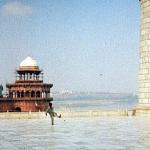

But surely the best evidence of Jahan's devotion is the Taj itself. Construction of it began only a year after his wife's death and continued for 23 years. In the meantime, her body was interred in Burhanpur until six months later it was transferred to Agra, site of the Taj. There her body was placed in a provisional sepulcher. Originally, Jahan had intended to build a replica of the white-marble Taj using black marble. The replica was to contain his remains, the Taj hers. The two were to be linked by a bridge spanning the cypress-lined Jumna river, on whose banks the present Taj now stands, and from whose waters Jahan, his court in tow, preferred to view it.

Unfortunately for posterity -- though perhaps fortunately for Jahan's subjects, who might have benefited from the 5 million rupees used to build the Taj, when they perished or resorted to cannibalism during the apocalyptic famine of 1630-1632 -- the replica was never completed. Jahan's attention was diverted by a war with his (and Mumtaz's) son Aurungzeb for control over the throne. Jahan was deposed in 1658 and died an ignominious death in captivity. The austere Aurungzeb, meanwhile, was little interested in monuments, especially to his father-turned-mortal foe. Thus Jahan's cenotaph appears in the Taj as a kind of an afterthought to the centrally located cenotaph of his beloved.

Jahan's reign is generally considered to be the Golden Age of Moghul rule, and Aurungzeb its swan song. The Taj fell into disrepair, and it wasn't until the British conquered India that the structure was again maintained, recognized for what it was, and duly appreciated. It seems that only a conqueror can understand the value of another conqueror's legacies.

While no one disagrees that Jahan is the structure's "producer" if you will, controversy remains regarding the identity of the "director" - its architect. According to Father Sebastian Manrique, a Spanish friar, the architect was a Venetian jeweler and silversmith named Geronimo Veroneo, the well-paid Moghul court artist. Others deny European workmanship, attributing the Taj instead to a man named Ustad 'Isa. This is justified in part by the Taj's digressing little, both in its overall plan and its main features, from other Moghul structures of the time. Its marble inlaid with precious stones (pietra dura), while striking, was apparently not innovative.

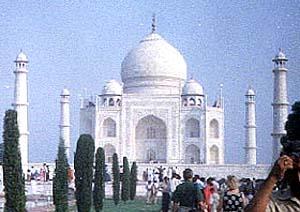

More striking even than the pietra dura, however, is the Taj's sheer size. Its bulbous dome, 58 feet in diameter, reaches a height of 187 feet, and can be seen well before one passes through the high wall girding the compound. The mausoleum rests on a 22-foot high plinth, on whose stones, much polished through years of traffic, visitors sit or play. At each corner stands a minaret topped by a kiosk.

Massive also is the compound, a rectangle oriented north-south, 1900 feet by 1000 feet. Within it is a garden 1000 feet square, lined with paths and quadrasected by a reflective canal. At the compound's southern end is an edifice, architecturally significant in its own right, serving as an entrance. On either side of the mausoleum are two identical buildings, the western serving as a mosque, the other formerly as a kind of guesthouse for visitors.

The tomb itself consists of an octagonal central hall and passages radiating outward from its corners. In the hall's marble wall is a lattice of gaps so small as to permit only a dim light; while the voices of those peering down into the sepulcher are heard to merge into an unearthly murmur perfectly suited to one's own meditations upon love, and love's mandatory end.

Many are drawn to the Taj by this mystique, at once romantic and somber; and many visitors are compelled to make declarations of love or its surcease. An Indian acquaintance of mine proposed marriage to his wife-to-be at the Taj; another acquaintance decided there to break up with his girlfriend. On one of my two visits I considered marriage, but - happily, so far - I was able to keep my wits about me.

Unfortunately, the pittance charged for entry at the time of those two visits has since been upped significantly. But the Taj can still be seen - and is perhaps better seen - as Jahan himself preferred to see it, from the Jumna river, perhaps at sunset when the dome assumes a color much like the blush of a person in love.

* * * * *

ThingsAsian

ThingsAsian